|

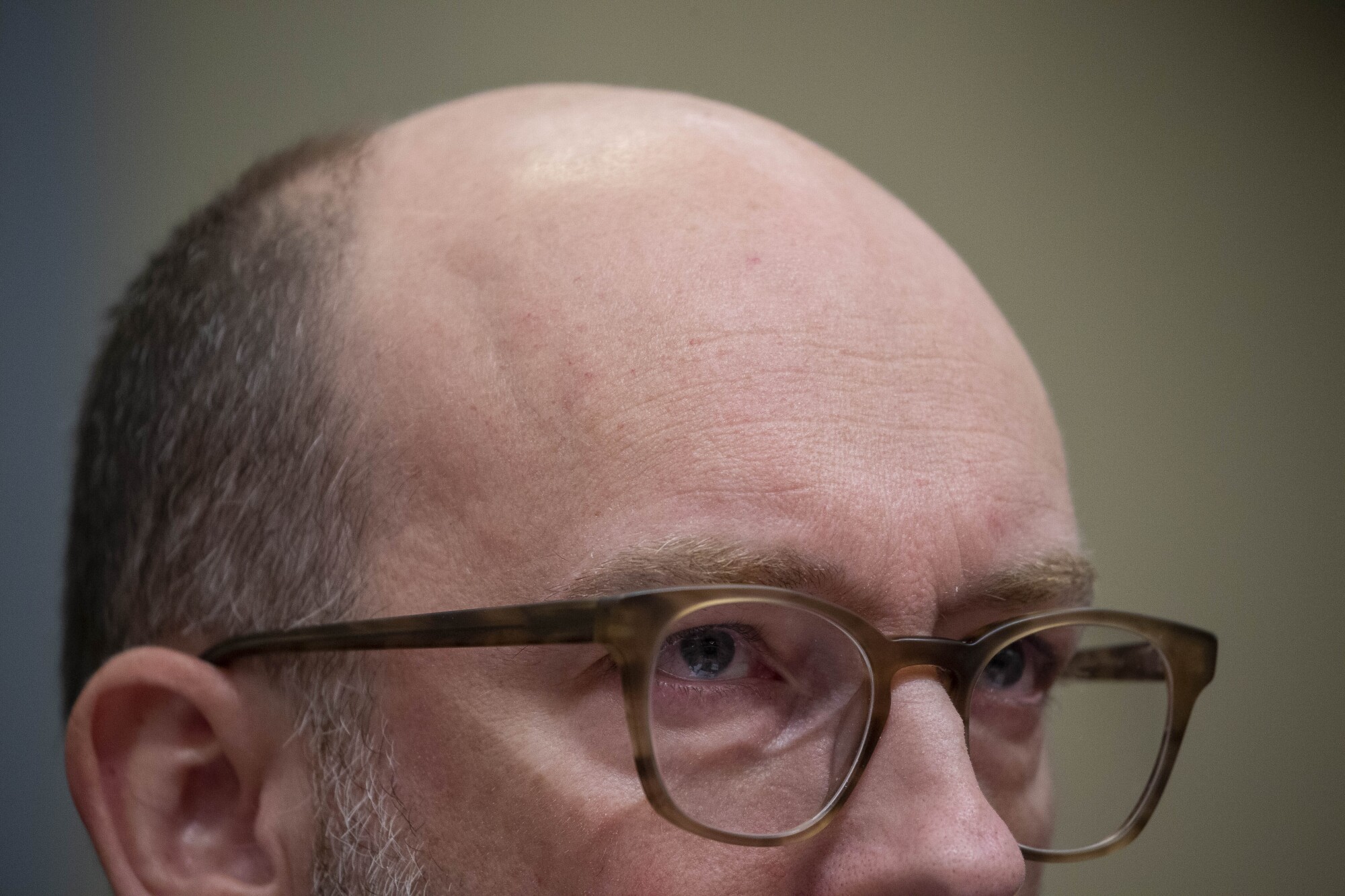

Alex Brandon/AP Photo

|

| TRUMP 2024 |

| ‘Conflict and Risk for Breakfast’: The Radical Wonk Who Could Run Trump’s White House |

| Editor’s note: NOTUS launches in January, but we’re giving you an early look at the kinds of stories we’ll produce. Today, we’re sending a profile of activist and former Trump official Russell Vought that is part of a series on people who would be influential in a second Trump administration. Vought is already one of the most powerful nonelected Republicans in Washington. If Trump wins, he may be headed for a top job — and a chance to put his self-proclaimed radical policy ideas into practice. Oh, did you miss our first story about the Biden campaign’s hopes to win North Carolina? Check it out here. And if you haven’t subscribed yet, please sign up for early access at NOTUS.org.

—

By Maggie Severns, Oriana González, Kate Nocera and Casey Murray Shortly after the 2022 midterm elections, Russell Vought — a former director of Donald Trump’s Office of Management and Budget — sat down in a makeshift podcasting studio in Matt Gaetz’s Longworth office and aired his grievances with House Republicans. Trim and bearded, wearing a blue-and-white checked shirt and tortoiseshell glasses, Vought explained that the problem with people like Kevin McCarthy was that they had been too afraid of brinkmanship to leverage the party’s potential power on Capitol Hill. They were too hesitant to verge on blowing the debt ceiling, and too scared to threaten a government shutdown to extract the changes necessary to course-correct the country. The problem, in Vought’s view, was not that Republicans’ cantankerous infighting had gone too far, but that it hadn’t gone far enough. “I loved working for Donald Trump because he ate conflict and risk for breakfast,” Vought said on the podcast, and he insisted that Republicans on the Hill needed to be willing to do the same. “When you fight, you become more powerful.” Eleven months later, Gaetz followed Vought’s playbook when he forced a vote that stripped McCarthy of the speaker’s gavel, plunging the House into weeks of chaos punctuated by multiple attempts to elect a new speaker and ultimately leading to the election of Rep. Mike Johnson (R-La.), a hardline Christian conservative. Next on Vought’s agenda: the White House. Vought is one of the most powerful nonelected Republicans in Washington — not only a close adviser to lawmakers like Gaetz and members of the House Freedom Caucus but also a leading ally of Donald Trump. Increasingly, Vought spends his days planning for the former president’s return. He leads a think tank called the Center for Renewing America that employs Trump allies like lawyer Jeff Clark, and he works with Project 2025, a conservative coalition created by the Heritage Foundation that includes other key MAGA personnel, such as John McEntee and Stephen Miller. Several Republican strategists and lawmakers interviewed for this story floated Vought as a potential pick for a White House role if a Republican, likely Trump, wins in 2024 — possibly even chief of staff. “He did a great job at OMB under President Trump, and he’d be great in a future administration,” said Rep. Chip Roy (R-Texas), who described Vought to NOTUS as “a friend” with whom he speaks “regularly.” A top role at the White House would give Vought a perch for pushing his most controversial plans. In recent months, he has proposed trying to find out whether potential immigrants “have any sense of the Judeo-Christian worldview that this country was founded on.” He also wants to convert swaths of the federal workforce to “Schedule F” status, meaning that they could be fired by the president. It’s a concept that could upend the entire machinery of U.S. government and one that Vought has been trying to bring to fruition for years: At the end of the Trump presidency, he proposed reclassifying close to 90% of civil servants working at OMB as Schedule F employees, though he ultimately ran out of time to complete the overhaul. “He wants power because he feels like, for decades, people have been ignoring his policy advice, or preferred policy solutions, and he’s had no way to implement them,” said one former colleague. “Now he sees Trump as the vehicle.”

***

Vought was born in Westchester County, New York, and attended evangelical Wheaton College before moving to Washington, where he landed an internship working for Rep. Christopher Shays (R-Conn.) in 1998. It was the start of over a decade of service in Congress. His first real taste of power was as policy director working under Mike Pence nearly 15 years ago, when Pence — then a member of Congress representing Indiana — held the title of Republican Conference chairman, making him the third-most-powerful Republican in the House. The two shared a passion for both conservative politics and religion. Like Pence, Vought is an evangelical Christian; when he later joined the White House, he attended a morning Bible study with other administration officials. Working out of a winding suite of offices reserved for top aides in the U.S. Capitol, just steps from the House floor, Vought spent his time on Pence’s staff hashing out decisions on how GOP leaders would tackle budgets and policymaking. Like his boss, Vought pushed fiscal conservatism — but he did it behind closed doors, working with aides to Minority Leader John Boehner (R-Ohio) and Minority Whip Eric Cantor (R-Va.). Then, in the summer of 2010, Vought bewildered the leadership team when, seemingly out of nowhere, he quit. Two days after leaving his job, he published a post on RedState, a blog run by conservative radio star Erick Erickson, saying House Republicans lacked a “bold” approach to cutting spending. “Some will say that it does not make political sense to call for these types of reforms before an election that is supposed to be about Democrats,” Vought wrote, but Republicans need to try to “solve the problems of the day and not simply make them modestly better.” He called on increasingly vocal Tea Party protestors to show up to members’ town halls and “tell them to go big or go home.” Aides to Cantor and Boehner were shocked. Just days earlier, Vought had been at the table. Now he was recasting himself as a provocateur. “Any big decision the leadership team made, he had been part of the process,” said a former Republican aide who worked regularly with Vought. “Nobody had thought of him as an outsider.” Vought, it turned out, was just getting started. He took a job as political director at Heritage Action, the burgeoning activist arm of the Heritage Foundation. As the Tea Party gained momentum, Heritage Action became its extension in Washington, working to harness the power of the new right wing. Vought spent countless hours building a base of grassroots supporters willing to call their members of Congress and attend town halls. The organization launched a scorecard that graded lawmakers on their conservatism, leaving many afraid that scoring poorly would attract a Tea Party challenge. In 2013, Heritage Action threw its new weight behind a spending bill that would have defunded Obamacare. The bill was guaranteed to fail in the Democratic Senate as the government ran out of money, which sparked a government shutdown that lasted 16 days and threw Washington into chaos. When it came to moving the party right, working on the outside as a tormentor of Congress proved to be just as effective for Vought as being an aide on the inside — if not more so. Pence, Vought’s former boss in the House, helped guide Vought into the Trump administration. Nominated to be deputy director of OMB in 2017, Vought found himself for the first time thrust into a role as a public figure. His deep religious conviction was on display when he appeared before the Senate at a confirmation hearing. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) questioned Vought over an op-ed he’d authored defending Wheaton College’s decision to fire a professor who had written on Facebook that Christians and Muslims are both “people of the book.” In the essay, Vought declared that Muslims have a “deficient theology.” “They do not know God because they have rejected Jesus Christ his Son, and they stand condemned,” he wrote. At the hearing, Sanders asked Vought if his comments were Islamophobic. “I’m a Christian,” Vought replied. “And I believe in a Christian set of principles based on my faith.” Incensed by what he saw as an attack on religious liberty, Sanders repeatedly interrupted Vought and kept drilling into his ideas: “What about Jews? Do they stand condemned, too?” Sanders asked. “Senator,” Vought said, “I’m a Christian.” “I understand you are a Christian,” Sanders bellowed, losing his temper while Vought sat silently in the hot seat. “But there are other people who have different religions in this country and around the world.” Vought eventually said that, as a Christian, he believed “all individuals are made in the image of God and are worthy of dignity and respect regardless of their religious beliefs. I believe, as a Christian, that’s how I should treat all individuals.” The exchange prompted debate over whether Sanders had tried to use a religious test for potential appointees. Vought was eventually confirmed — with Vice President Pence casting the deciding vote.

***

Vought’s prescription for the federal government centers on the idea that we are living in an era that has abandoned the Constitution, necessitating the use of radical means — including unorthodox interpretations of the law or massive disruptions like government shutdowns — to save democracy. He frequently defends Christian nationalism and promotes a vision in which the government would abandon neutrality toward religion. He declined multiple interview requests from NOTUS but has laid out his point of view in essays, speeches and interviews, on the social media platform X, and in conversation with others who were interviewed for this story. According to Vought, a central goal of the next Republican administration should be to dramatically curtail the independent power of the federal bureaucracy and guarantee that the power of the executive branch rests with the president and “chosen advisers” whose priority is to further the president’s agenda. The job of a conservative president has been made more difficult, in part, by “Congress’s decades-long tendency to delegate its lawmaking power to agency bureaucracies,” he wrote in Heritage’s Project 2025 policy agenda, a 920-page guidebook for the next Republican administration that Vought and others have assembled. In a 2022 essay, Vought wrote: “The Left in the U.S. doesn’t want an energetic president with the power to bend the executive branch to the will of the American people. They don’t want a vibrant Congress where great questions are debated and decided in front of the American people and the tradeoffs made there. They don’t want empowered members. They want discouraged and bored back benchers. They want all-empowered career ‘experts’ like Tony Fauci to wield power behind the curtains. And in America, the scary part is that this regime is now increasingly arrayed against the American people. It is both woke and weaponized. The national security state, with organs like the FBI, NSA, and CIA, are aligned against the American people, who are outraged by this revolution they never assented to. ... The hour is late and time is of the essence to expose the charade, rally the country against it toward self-government once again, and seize every leverage point to arrest the damage.” In order to rein in the bureaucracy, Vought has advocated for the House to embrace the Holman rule, which allows lawmakers to defund specific government jobs through the appropriations process. His embrace of converting federal jobs to Schedule F would similarly transform the federal bureaucracy — and, critics say, it could serve as a means for Trump to punish those Americans who disagree with him. “It would totally destroy 140 years of insulating the civil service from partisan matters. I’m telling you, the real risk is not only that we reintroduce the spoil system but what that leads to in terms of services provided” by the government, said Rep. Gerry Connolly (D-Va.), who sparred with Vought during the Trump administration and is the former chair of the subcommittee in charge of the civil service. “Do you want to go to a system where you get served based on your politics? Think about that.” Vought acknowledges some of his policy ideas would break with legal tradition. To promote the president’s agenda, he argues, the OMB should have a general counsel who is “respected yet creative and fearless” enough to challenge “legal precedents that serve to protect the status quo.” When it comes to spending, Vought has said that the federal government should leave Social Security and Medicare intact but slash a plethora of government agencies. He aims to “flip the policy debate” so health or education programs have to “prove their own worth” in order to receive funding. Vought’s views on immigration are equally arresting. “It is an America-first principle to be able to have a conversation about the types of people that we want to be here,” he said in a recent interview with the advocacy group Restoration of America, adding that he would want the government to attempt to learn what immigrants know about the “Judeo-Christian worldview.” “That doesn’t mean we don’t give religious liberty,” he continued. “But it does mean, are they wanting to come here and assimilate?” Vought, in short, does not lack for proposals. And yet he is not just an ideas man: He excels at selling concepts that may seem outrageous at first to his peers. “He understands the reality of what’s possible,” former White House press secretary Sean Spicer told NOTUS. “You have to have a comfort level that the person telling you to jump off the diving board knows there’s water below. Russ can explain to people, ‘Hey, there is water below, you can jump.’” Rep. Randy Weber (R-Texas), a member of the House Freedom Caucus, told NOTUS, “I do value his opinion. And I think the others [in the Freedom Caucus] do as well.” During the Trump administration, Vought earned accolades for his willingness to take unorthodox steps that helped the president. It was Vought’s OMB that put an official hold on aid money to Ukraine in 2019, a move that investigators probed during the first Trump impeachment and led Congress to subpoena Vought. He called the inquiry a “sham process” and refused to testify — then got confirmed as OMB director the following year. “There’s a class of people who served [under Trump] for four years at senior levels — those who weathered the storm in senior positions,” Spicer said. “Russ is clearly high on that list.”

***

In recent months, Vought has been on a media spree. In addition to his regular rotation through right-wing podcasts like Steve Bannon’s “War Room” and “The Glenn Beck Program,” Vought and his collaborators at Project 2025 have been previewing their strategy for the next administration to more mainstream outlets like NPR, The Washington Post and The New York Times. In the Times, Vought said too many lawyers on the right are unwilling to challenge convention and claimed the notoriously conservative Federalist Society “doesn’t know what time it is.” This ubiquity in the press has led Washington Republicans to ask: What does Russ Vought want? Republicans who have worked with Vought say it’s possible that he wants to be White House chief of staff. After all, other former OMB directors have ended up in that role: Mick Mulvaney, Trump’s first OMB director and a friend of Vought’s, served as acting chief of staff from 2019 to 2020; and President Biden’s current chief of staff, Jeff Zients, served as acting OMB director for President Barack Obama in 2010 and from 2012 to 2013. Vought could be offered a more nebulous White House job, such as “senior adviser” or “counsel” to the president. Trump could try to nominate Vought for a cabinet post, but such a position would require him to again pass Senate confirmation — and it’s not clear he could garner the votes needed this time around. “There is a sense amongst a lot of people aside from House conservative hardliners that getting him confirmed would be a challenge,” said one aide who worked for the first Trump administration. “He would need to be in a senior position, but a West Wing position that doesn’t require confirmation.” Of course, Trump’s opinions of aides can change rapidly, making it hard to guess who will ascend to power if he wins another term. And as a slew of stories reporting on the next administration popped up online in recent weeks, the Trump campaign has twice tried to tamp down chatter about what the White House will look like if Trump wins. “Let us be very specific here: unless a message is coming directly from President Trump or an authorized member of his campaign team, no aspect of future presidential staffing or policy announcements should be deemed official,” Trump campaign advisers Susie Wiles and Chris LaCivita said in a statement issued to the press. “He is not interested in, nor does he condone, selfish efforts by ‘desk hunters.’” Vought, who obsesses about policy and procedure, is in some ways a strange fit for Trump. Yet his fealty through the aftermath of the Jan. 6 attacks and willingness to help Trump buck convention make him a valuable player in the former president’s orbit, according to Trump allies. Now firmly planted in Trumpworld, Vought is no longer close to many of his former confidants — including Pence, according to multiple people in touch with the former vice president. (“Mike will always respect Russ’ service and intellect,” said Marc Short, a longtime adviser to Pence.) Vought’s considerable influence on the ever-more-powerful far-right flank of the Republican Party, however, is clear. Recently, outside the House floor, NOTUS asked Gaetz about Vought and his trajectory within the GOP. Without hesitating, Gaetz pointed to his interview with Vought before retreating into an elevator. “You should just watch his episode,” Gaetz said, “on the 52nd most popular political podcast!” — Maggie Severns and Oriana González are reporters at NOTUS. Kate Nocera is a managing editor at NOTUS. Casey Murray is a NOTUS reporter and an Allbritton Journalism Institute fellow. |

|

© 2024 Allbritton Journalism Institute |