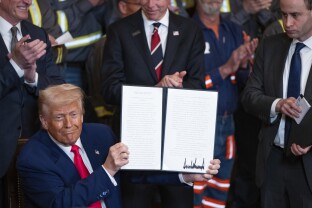

President Donald Trump’s decision to invoke little-used emergency powers to bolster the American coal industry left energy analysts alarmed and uncertain about what would happen next.

Kent Chandler, the former chair of the public service commission in Kentucky and now a fellow at the center-right R Street Institute, found himself having flashbacks.

Many phrases and concepts in the executive order almost exactly mirror those in a law passed in Kentucky in 2023 — which the coal industry lobbied for — that uses the declaration of an emergency to make it difficult for coal plants to retire. That law employs similar language of reserve margins, discussion of fuel source and mix and other technical specifics in Trump’s Tuesday executive order, which invokes the emergency powers section of the 1935 Federal Power Act, called section 202.

“This is effectively a section 202 nationwide version of the legislation that they passed in Kentucky,” Chandler said. “I would be very surprised if the folks in the administration that had conversations with the industry about what to do on this front weren’t aware of this legislation.”

Other states like Utah, West Virginia and Montana have passed laws in recent years that make it more difficult to close coal plants, but the specific language of the Kentucky law is much closer to the executive order than those of other states.

The White House referred NOTUS to the official fact-sheet on the order when asked about its origin.

Trump’s order directs the Department of Energy to take an emergency power that’s normally used in brief moments of crisis and apply it instead for his own political goal of extending the life of certain power plants. While the order itself does not mention coal power, most plants that have retired recently are coal-fired, as are most plants scheduled to shut down in the coming years.

Energy analysts told NOTUS that the order sets an alarming precedent for politicizing the emergency authority critical for true disasters in the power system.

“The process has been a nonpartisan emergency good governance provision through the entire history of the Federal Power Act,” said Abe Silverman, an energy researcher at Johns Hopkins University and the former general counsel for the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities. “It would be a real shame to politicize the 202(c) process (the emergency process) and make it into an instrument of political policy making, and lose the really important reliability function that 202(c) provides.”

Since 2020, the emergency provision of the Federal Power Act has been used 13 times, entirely in response to extreme weather events or to help California address an energy crisis. Each time, the Energy Department has given orders for power plants to operate outside their normal conditions, in order to prevent a blackout or grid collapse.

Tuesday’s executive order requires the department to do something entirely different with its emergency power, duplicating what utilities and regulators have already been doing for decades. The DOE must come up with its own models for assessing how much power the country needs in reserve, and possibly prevent power plants — most of which would be coal — from shutting down if doing so would lower the reserves.

“The emergency orders are used to address short-term concerns from extreme weather events. The Trump administration is trying to apply this tool to a different issue, for keeping plants online a lot longer. There’s not a precedent,” said Timothy Fox, the managing director at the research analysis firm Clearview Energy Partners.

In many ways, the specifics of the order confused analysts, who said it’s clear that the administration wants to support the coal industry but unclear how the order could actually do so over the longer term.

The American coal industry is in a marked decline, with plants continuing to shutter every year because coal cannot compete economically with other sources of power, especially natural gas. Nearly 5% of all U.S. coal power is expected to shut down in 2025 alone. Energy analysts don’t foresee this order, or any of the other coal-related executive actions Trump signed on Tuesday, preventing the industry’s continued fall. Trump similarly tried to bolster the coal industry during his first term, but even more aggressive attempts then failed to change the economics.

“This is a trend that’s been in force for decades that has a lot of macroeconomic factors that are driving it. When it comes to emergency powers, you can get more stuff consumed, but you cannot get more stuff built, right? So maybe you have existing coal plants that operate at a higher capacity level for the short term. But it doesn’t seem like anyone’s running to build a new coal plant,” Fox said.

The Kentucky law has already slowed the retirement of coal plants. During Chandler’s tenure, the commission, in accordance with the new law, ordered that two coal plants scheduled to retire would instead remain in use. “It was significant,” Chandler said.

Duke Energy, an electric service provider that operates in Kentucky, lobbied against the bill before it passed and again against an update. The company said that the law would make it hard to close Duke coal plants that are already scheduled for future retirement, significantly increasing costs for consumers.

Now that Trump has essentially nationalized the policy, Devin Hartman, the director of energy and environmental policy at the R Street Institute, said he’s been fielding conversations all day with industry insiders who share the same alarm.

“As a matter of governance, it’s bad. There’s just no way to slice and dice it. There is no evidence of a grid emergency,” Hartman said of the order. “It sets a really bad precedent for future administrations. It creates a lot of opportunity for political side-agendas to undermine evidence-based industry practices.”

Because utilities, regional grid organizers and government regulators already assess reserves and make decisions about whether a plant can close, anything that the Energy Department produces would be duplicative at best or confusing and contradictory at worst, analysts said.

If the department’s methodology seriously differs from those that already exist, “you could end up with some potentially very, very expensive power plants that are, under the more traditional engineering reliability analysis, superfluous. And so the cost of those new units could be very high,” Silverman said.

In the worst case scenario, a methodology that seriously diverges from the industry standards could also send confusing signals into the market about whether companies should be investing in new power generation in the first place. That’s the last thing that the grid needs, with electricity demand forecast to grow for the first time in decades and new power generation already coming online slower than forecast, Hartman said.

—

Anna Kramer is a reporter at NOTUS.

Sign in

Log into your free account with your email. Don’t have one?

Check your email for a one-time code.

We sent a 4-digit code to . Enter the pin to confirm your account.

New code will be available in 1:00

Let’s try this again.

We encountered an error with the passcode sent to . Please reenter your email.