MILWAUKEE – Little has changed in Wisconsin to facilitate a faster vote count since 2020, and election leaders in the state’s biggest and bluest cities — where ballots take the longest to count — are bracing for another onslaught of attacks.

Voting rights advocates and political leaders told NOTUS they’re concerned the small handful of changes the state could have made to mitigate some of the disinformation around election results didn’t happen — and those wanting to discredit elections will again weaponize anything they can.

In the wee hours of the all-night vote count in Milwaukee four years ago, Donald Trump was already laying the groundwork for the onslaught of lawsuits, personal attacks and misinformation to come.

“We are up BIG, but they are trying to STEAL the Election,” Trump wrote on X at 1 a.m., after most states were called and four hours before Milwaukee’s election results came in. In the morning, Trump posted multiple times about “ballot dumps” in swing states going for Biden, but those were just absentee ballots getting counted on Election Day, as Wisconsin (and a few other states) require.

This year, the Milwaukee count is again expected to take place in the middle of the night. State lawmakers failed to pass a bill that would have allowed election clerks to start processing absentee ballots before Election Day.

“We were one of the only states that didn’t adjust any election laws,” Claire Woodall, former executive director of Milwaukee’s election commission and current senior adviser at the civic-advocacy group Issue One, told NOTUS. “One really pivotal thing that we really wanted to get passed had bipartisan support for was early processing of absentee ballots.”

There’s an added layer for those wanting to cast doubt on Milwaukee’s election results: A new executive director of the city’s election commission was appointed this year; she has never run a federal general election before and there was internal turmoil over her ascent.

In the absence of any legal changes to improve trust in elections, election leaders told NOTUS they’re beefing up where they can — increasing security, ensuring election observers have access to watch the count and trying to stay as nonpolitical as possible.

In a race that could be decided by a few thousand Wisconsin voters — or could switch on the margins of the state’s blue hubs — there’s an undeniable tension, and pressure, landing on the heads of the small handful of workers tasked with delivering the results. “You’re constantly triaging how to limit conspiracy theories,” Woodall said. “But it’s like the conspiracy theories are going to come no matter what.”

***

As some swing states took steps to close loopholes that election deniers capitalized on in 2020, Wisconsin’s state Assembly was, by and large, stuck in a political deadlock.

“We would have loved to have been able to ratchet down the disinformation,” the voting rights advocate Jay Heck told NOTUS, “but I think part of the problem here has been the political configuration in the legislature. Overwhelming conservative majorities in the legislature have made it difficult to try to change the basic rules.”

He also pointed to a unique shift in Wisconsin he sees as contributing to partisan struggle. In 2016, the state dissolved its government-accountability board. The board, which was made up of former judges, oversaw elections. It was replaced with an election commission made up of party-affiliated commissioners. The move was opposed by Democrats.

“We tried this year to get stronger rules for election observers,” such as those detailing where observers can stand and what they’re limited from doing, Heck, who works for Common Cause Wisconsin, said.

“Unfortunately, just because of some of the deadlock in the commission, they’re not going to be put into place until after Nov. 5.”

In the state legislature, the bill that likely would have had the biggest effect on the election would have allowed election officials to start processing absentee ballots the Monday before Election Day. It garnered bipartisan support in one branch of the state’s legislature but the Republican-led Senate failed to take it up. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported that the state Senate’s Republican elections committee chairman refused to advance the bill after a fellow GOP Assembly member said “there are concerns with the chain of custody of ballots and the hearing revealed the disparity of partisan observers of central count processing.” Devin LeMahieu, the Republican Senate majority leader, didn’t push for a vote on the bill despite supporting the change in 2020.

“This is the one thing that would have made our elections run a little smoother,” Chris Sinicki, a Democratic state representative from Milwaukee and county party chair, told NOTUS. Milwaukee’s Republican Party chair did not respond to an interview request.

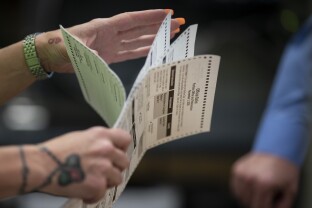

Processing absentee ballots is significantly more time consuming than those cast in person, which can be counted in real time. Manual steps like opening the envelope, reviewing the ballot for valid signatures and checking for an address all take time and manpower to process. Wisconsin is one of fewer than 10 states that doesn’t start processing absentee ballots until Election Day, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. (Pennsylvania is another.)

Meanwhile, Republicans in Wisconsin’s last legislative session introduced at least 26 bills running the gamut of alleged security concerns, including terminating the state’s relationship with the Electronic Registration Information Center and mandating audits after general elections.

“The things that the Republicans here concentrated on really would not have made our elections any smoother or any cleaner,” Sinicki said. Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, clearly agreed: He vetoed a historic number of Republican-led election bills that made it to his desk, which were largely aimed at restricting ballot access.

One of the few major changes to Wisconsin elections this year — a ban on private funding for election administration — was decided by voters via a state ballot amendmendment this spring.

The change sprung from unfounded allegations by Republicans and election deniers that grants from a Mark Zuckerberg-backed organization — so-called “Zuckerbucks” — had swayed election results. Milwaukee leaders that spoke to NOTUS said the loss of private grants simply means less resources for the small staff that administers elections, pulling all-nighters to count ballots.

“It’s such an intricate, detailed job and, like, in Milwaukee, they only have 11 full-time permanent positions,” Woodall, the city’s former election commission director, said. “Nothing has changed because they just don’t have time. We haven’t seen an increase in funding, instead there was a limit on accepting grant funding.” She said she used the last round of private grant funding this spring, before the grant-funding change took effect, to beef up security and help dispel misinformation claims. That included putting 20 cameras in at the operations center — there was one camera in 2020 — adding badge access to get into certain rooms and installing iron grates on windows.

In Madison, Wisconsin’s second-largest city, the city clerk, Maribeth Witzel-Behl, served as clerk in 2020, so she knows what to expect.

She said changing legalities over the years have made things more complicated not just for clerks, but for voters too. The state’s Supreme Court has re-adjudicated recent elections-related cases, including a July decision that reversed a 2022 ruling barring most absentee ballot boxes.

“Election laws have become more complex, and voters have experienced that too. So it’s not just that the political environment has changed,” she told NOTUS. “There are questions that voters will contact us with because it’s time to figure out how to navigate new rules that are in place from court cases or new laws.”

But ultimately, she said distrust flows in from outside the city. For example, when an error in Madison’s clerking office allowed duplicate ballots to get sent out in late September, Congressional Rep. Tom Tiffany falsely suggested the clerk’s office might be engaging in impropriety. The city of Madison does not fall in his district.

Witzel-Behl sent a response to Rep. Tiffany explaining the error and the safeguards put in place to make sure those voters wouldn’t be able to vote twice. But Tiffany continued on the offensive, ultimately calling for an investigation. His first post on X on the subject has 2.5 million views.

“I think the people who don’t trust us are people who are not in our own community, and so the nasty messages that we get, they’re not Madisonians. They are from outside of our municipality, outside of our county, maybe outside of our state. There’s nothing we can do to affect how they might view us,” Witzel-Behl said.

But in some ways that’s helpful because her primary job isn’t in service to outsiders, it’s to her constituency whose vote she handles.

“They know they come here when they need notary services or they have a question about local government, they’ll give us a call. And so that helps with building trust within the community, and then outside of the community, that’s not really our focus,” she said.

***

Regardless of legislative and legal action, some of the most pointed attacks may come down to personnel, particularly in Milwaukee where major changes could fuel attacks for those already wanting to sow doubt in the election process.

For one, Woodall’s former deputy director, Kimberly Zapata, was convicted on felony charges of obtaining fake absentee ballots ahead of the 2022 midterm elections. (The ballots were not cast, she instead sent them to a state legislator as a demonstration.)

Separately, long after Zapata was already replaced, Milwaukee’s mayor suddenly — and unexpectedly, per Woodall — decided not to reappoint her as executive director in May, just six months before the November election.

The new deputy chief, Paulina Gutierrez, who was hired in 2023 and has never run a federal general election, was granted the role instead. In the days after the decision, election commission staff raised concerns about Gutierrez’s “ability to successfully lead our team,” according to records obtained by Votebeat Wisconsin.

Gutierrez’s office did not make her available for an interview. “Unfortunately, Paulina is currently immersed in critical preparations and unavailable for interviews,” it said, and it did not respond to a request for comment by the time of publishing. Gutierrez previously told the Associated Press, “I’m feeling really confident my staff and I are ready.”

The chair of Milwaukee’s election commission, Terrell Martin, told NOTUS he’s confident in Gutierrez.

Martin said he’s gone to great lengths to avoid allegations of political bias in an effort to eliminate any gaps for potential attacks. Even though he was selected by the Democratic Party, he does not endorse candidates. (Milwaukee is unique from the rest of the state because it has a nonpartisan, mayor-appointed executive director for elections and three election commissioners chosen by political parties — currently two Democrats and one Republican — with the distribution based on which party received the most votes for governor in the county.)

But Martin acknowledged that misinformation would likely proliferate regardless of how smoothly the election runs, pointing to the allegations that out-of-staters stuffed ballot boxes in 2020. In reality, the election commission had to rent cars for workers, often with out-of-state license plates, to pick up ballots.

Joe Oslund, communications director for the Democratic Party of Wisconsin, told NOTUS the party would “have a record number of poll observers on the ground in precincts statewide on election day to ensure that everything is running smoothly.” As leaders sweat over the attacks that may come, nearly everyone who spoke to NOTUS emphasized that though some changes may have helped, combating so much misinformation feels futile.

“The disinformation that comes from losing candidates in the aftermath of the election depends on one factor and one factor only, the fact that they lost,” David Becker, executive director of the Center for Election Innovation and Research, said.

—

Claire Heddles and Nuha Dolby are reporters at NOTUS and Allbritton Journalism Institute fellows.

Sign in

Log into your free account with your email. Don’t have one?

Check your email for a one-time code.

We sent a 4-digit code to . Enter the pin to confirm your account.

New code will be available in 1:00

Let’s try this again.

We encountered an error with the passcode sent to . Please reenter your email.